Life in the Air Force meant total immersion in the business of flying. There had been intensive training with much of his time spent at the navigation school in Rivers, Manitoba. His flying had progressed from dual to single control Finchs and Harvards and then to Ansons and heavier-multi-engine crafts. In January of 1943 he was promoted to Flying Officer and in November of the same year he took the big personal step of marrying Patricia Hopper in the Y.M.C.A. in Windsor, Ontario. Why the Y.M.C.A.? Well it was just there and they were in a hurry. One month later on 16 November he embarked from New York for England and he had not been home since. After spending time in a heavy conversion unit to train on a Halifax he was promoted to Flight Lieutenant in July, 1944. Despite the personal pride he took in getting this promotion it was not a time to celebrate because he had also received word that his mother had died that month. She had been suffering terribly from cancer and the family requested that he be given leave to come home and visit with her before she passed away. The War Office was sympathetic but would not allow a leave because of the pressing requirement for new aircrews in Bomber Command. Jim was put on strength with No. 434 Bluenose squadron on 25 October, 1944.

At 24 years of age he now had a mountain of responsibility on his shoulders. He had always tried to make up for his missing father in the family setting but this was different. He was not only in command of the aircraft but he was responsible for the lives of his six crew members who had become closer than family over the short time he had known them. Down in the nose of the plane was Flight Sergeant Allan Kurtzhals from Vancouver, B.C. also 24 years old but single. He would spend most of the flight today in a prone position trying to be comfortable. It was his job to guide the plane on the bombing run and release the bombs at the right point to hit the target. This was not a minor accomplishment considering the plane would be flying at around 20,000 feet at a speed of approximately 300 miles per hour. To make the job more difficult, consideration had to be given to cross winds and the aerodynamics of the ordinance being dropped. If required he would also have to get up and fire the machine gun mounted in the nose of the aircraft.

In the small compartment about a metre square behind the bomb aimer sat the navigator, Harry Pearce, from Drumheller, Alberta. At 28, and also married, Harry shared the status of being the oldest member of the crew. Jim and Harry had been together in the 1664 Heavy Conversion Unit and it wasn’t easy to forget the close call Harry experienced earlier in the year. On a night training flight out of Dishforth on 15 April his plane was caught in an intense storm on its return to base. The two port engines on the Halifax had failed so they were given permission to land despite a 10 mph tail wind. On breaking through the cloud cover the pilot realised that he had overshot the runway and tried to rescue the situation by putting down on an adjacent field at Topcliffe. Unfortunately the plane clipped a cottage on its descent and crashed. Harry and air gunner John Tyinski were the only two out of the seven to survive the impact and fire that followed. It had taken several months for Harry to recover from his injuries but he could not forget the loss of his friends. Harry’s small area was crowded with navigational aids; a G-set for radio navigation, an H2S (code word for ground scan radar) cathode ray screen, air and ground speed indicators, a dead-reckoner and a compass. There was an overhead fluorescent light, a small desktop and a chart rack all designed to bolt down so as not to fly around when violent evasive action was required. In the early days of the war navigation was a very hit and miss endeavour but by December of 1944 there had been a lot of progress with electronic beacons and the use of the Pathfinder Force to act as the navigational leaders of each mission.

Harry Pearce

Behind the navigator and almost directly below the pilot sat the Wireless Operator. P/O Bert Brown. Bert was also 28 and had lived in Wetaskiwin, Alberta before the war. His father was a partner in a car dealership and Bert probably had visions of returning home to take part in the family business. He could think about settling down with Cora, the girl he had married in February 1943 just before he left for overseas. It was all too clear to Bert that his future was not exactly a foregone conclusion because he had already been in two training crashes back in Canada. He survived a crash on Vancouver Island and then went down in another crash in freezing rain in Alberta. The plane dropped into a grain field and slid forever on the ice before coming to a halt. He, like Harry, had experienced what happens when things go wrong. He also had the worry of knowing that his younger brother Jack was missing in action. Jack was also an airman and had been missing for six months after flying in the North African theatre and Italy. It was a real concern for both him and his family.

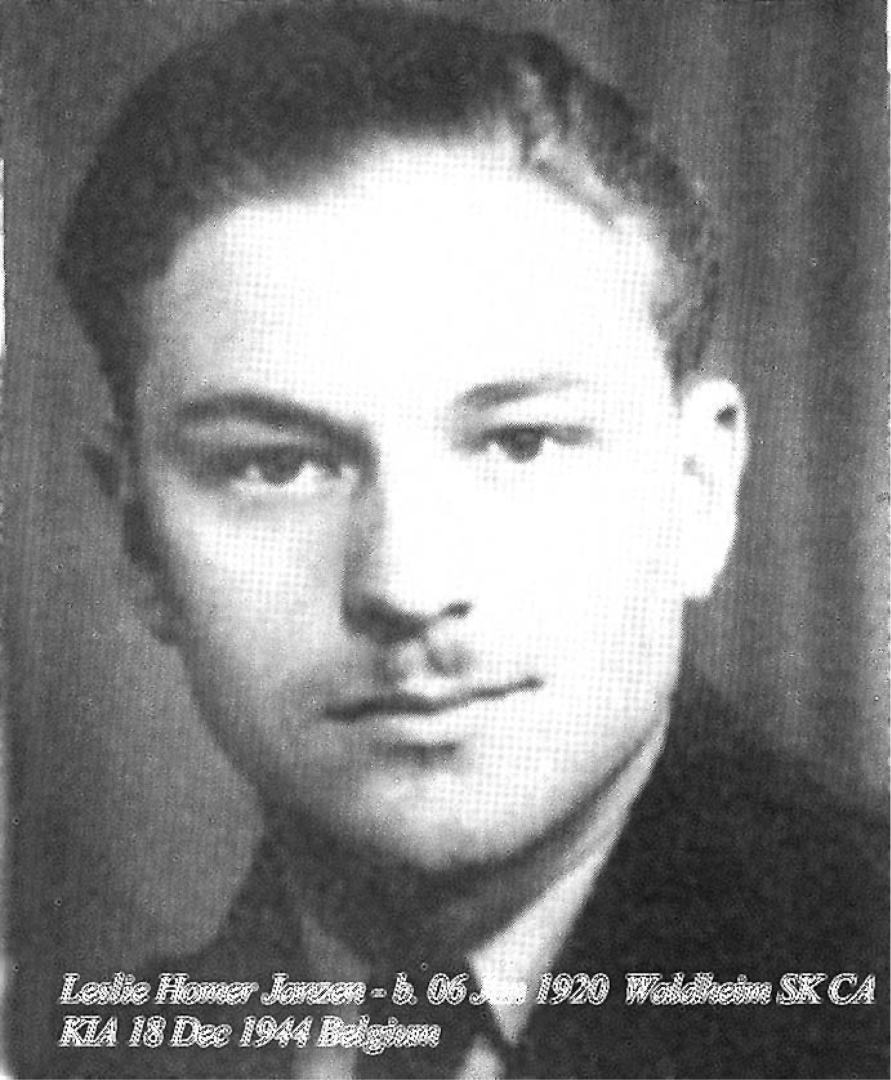

Sgt. Les Janzen occupied another compartment just behind the pilot. He was the flight engineer and it was his responsibility to monitor the mechanical workings of the aircraft. He had to constantly monitor the fuel situation and the condition of the engines. If the plane sustained flack damage or had engine problems Les would become very busy trying to jury rig something to get them home safely. On takeoffs, Les would reach over and control the centre-mounted throttles while the pilot fought to control the plane. It was a difficult and heavy job when the plane was fully loaded with fuel and ordinance. Les, who came from around Erwood, Saskatchewan was 24 years of age and single.

Leslie Homer Janzen

Two gun turrets provided the aircraft’s main defence against German fighters. There was an upper middle turret and the tail turret. Today, as in their previous four flights over Germany, F/Sgt. Gord Olafson would be manning the rear turret. Gord was another west-coaster who came from Stevenson, B.C. He had a cold and lonely position at the back of the aircraft and needless to say dangerous as well. This turret with its four .303 cal. Browning machine guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition was the main defence for the bomber. The German night-fighters tended to attack from the rear so Gord was in the direct line of fire. There had been occasions when a bomber would return undamaged except for having the rear turret completely shot away. Sometimes the gunners would remove the Perspex panel immediately in front of them in order to have a better view of an approaching fighter. It made their tiny compartment bitterly cold and the wind would be ferocious but for some gunners it was the only way to go. The earlier the detection of a fighter, the better the chance of the pilot pulling off a successful evasive “corkscrew” move and in most cases the warning came from the rear gunner. Gord was 23 years old and born in Stevenson, B. C. but his father Guttorm, a merchant seaman, was originally from Norway and his mother Barbara Witzgier was born in Germany and came to Canada before World War l. Gordon finished high school in 1941 and then went to work as a lineman for the Canadian Fishing Company for one year before enlisting in September 1942. At 5 ft. 9 in. tall and 121 lbs. he was ideally suited to fit into the rear turret. He had three brothers, Robert, Earnest and John who also enlisted and were serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Gord Olafson

The mid upper turret was manned by Flt./Sgt. Alex Divitcoff, the youngest member of the crew at 20. Alex was a Torontonian who came from Macedonian heritage who enlisted and began his training in the air in July of 1943 at the gunnery school in Macdonald, Manitoba. After an introduction to the cine gun camera he spent many rounds of ammunition firing at a moving beam target and an “over the tail” exercise. By the end of September he had spent 25 hours in the air and his initial training was over. By November he was in England and flying training flights in Wellingtons with the No. 82 O.T.U. This training involved day and night flights, cross country bombing circuits and air firing and by the time he was finished he had accumulated 69 hours of daylight flying and 45 hours of night flying. In February of 1944 Alex was assigned to the 1664 Heavy Conversion Unit and was training on Halifaxes based in Dishforth. He was assigned to several crews and it was not until the end of September that he joined Jim Parrott’s crew and he stayed with them when they were transferred to go “on strength” with 434 Squadron on 25 October. By this time Alex had 172 hours of daylight and 107 hours of night flying under his belt and he had excellent grades for his proficiency as a gunner. He had recently done two practice flights in the rear gunner position just before their last mission but today he would be in his familiar middle turret.

Alex Divitcoff